Hi! My name is Marty Snyderman.

As a new columnist for Sources, I would like to introduce myself and give you the Cliff’s Notes version of my professional background. I have made my living through underwater photography since the mid-1970s while working as a still photographer, cinematographer, teacher, author and presenter. Creating underwater images, helping others gain a better understanding of techniques that lead to consistent success and sharing the joy that underwater photography can bring are three of my passions in life.

I hope you will become a regular reader of this column and that the content helps you up your photographic game.

On numerous occasions over the years, I have had a student ask me something along the lines of what I think separates better underwater photographers from the rest of the pack. I preface my answer by saying, “You might be surprised, and even somewhat disappointed, by what I have to say, but if you think about my reply for a moment, you will understand where I am coming from and why.”

There are a number of ways to answer the question, but the factor that is most underappreciated is being a good diver. I think many students are looking for an answer that involves the latest, greatest piece of equipment or some unshared technique, and at first, they often doubt the validity of my answer.

If that describes you, please allow me to continue before making your final judgment.

By being a good diver, I am referring to mastering skills such as the ability to achieve and maintain neutral buoyancy quickly, both near the surface and at depth, to be able easily and quickly get into and hold your position in currents, minimize your movements, and manage your equipment and yourself so you avoid colliding with the substrate, stirring up bottom sediment or frightening your subject — and never, ever, running out of or so low on air that you put yourself or another diver in a potentially dangerous situation.

As I share my thoughts, it often seems to me that a lot of students think I must be talking about someone else, that I couldn’t possibly be talking to, or about, them. But let me be clear, I am talking to all of us. In fact, I am quite comfortable stating that mastering the skills required to be a good diver often separates those who consistently produce high-impact images from those who see the same subjects but don’t create memorable photographs.

Years of teaching and watching other photographers has made me equally comfortable in saying that often it is “more experienced” photographers who resist the thought that if they made the effort to become better divers by monitoring themselves, their images would improve as a by-product.

I hope my comments don’t come across as if I am preaching down to you or anyone else. That is something I would like to avoid. I am simply trying to share observations gleaned from my experience. So I stand by my comments that improving diving skills will lead to higher quality images, and I think this thought applies to a lot of us.

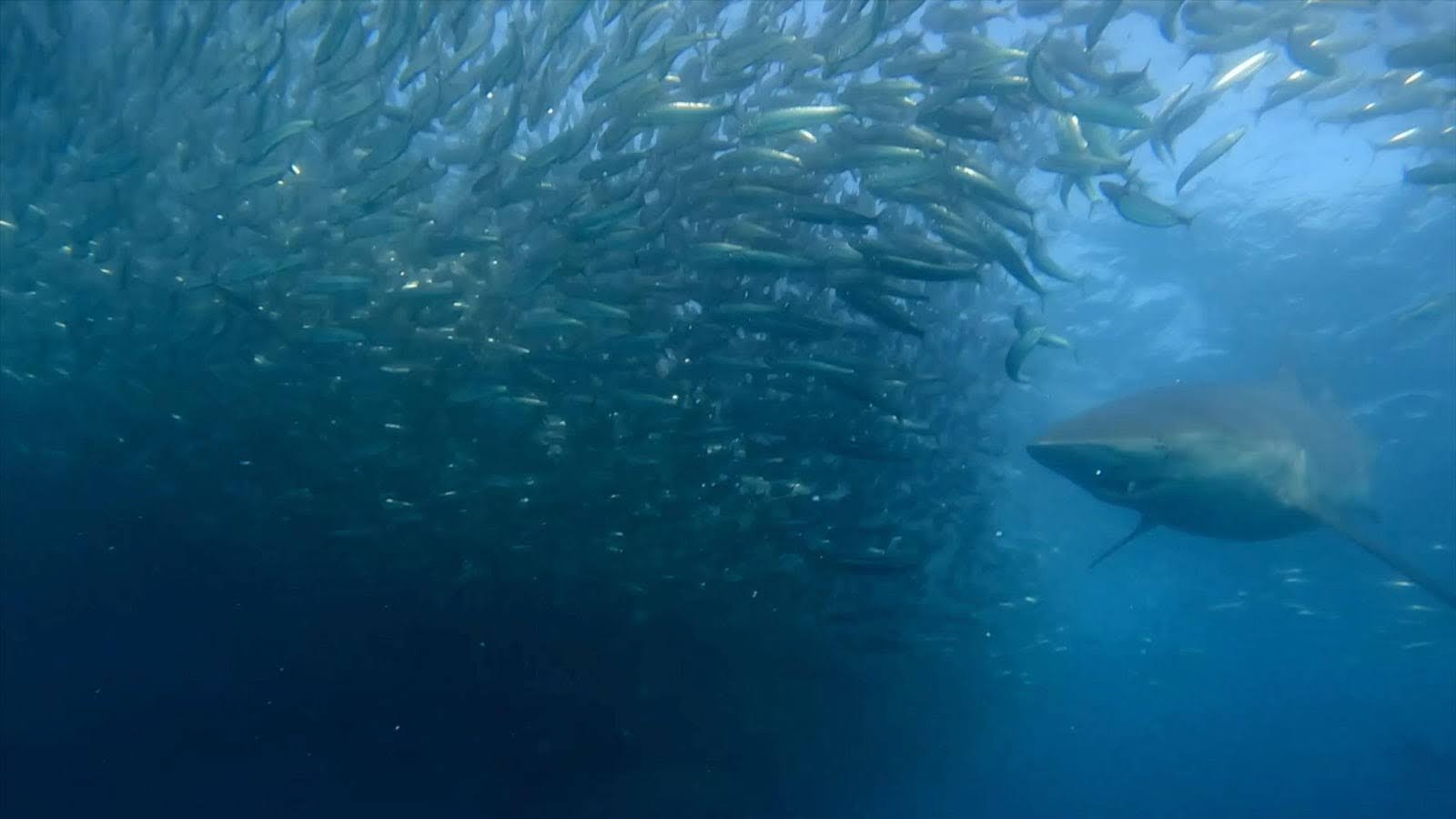

Consider just some of the things I needed to do when creating the images featured in this piece. For starters, to create the image of the coconut octopus, I needed to get close to the easily stirred-up, sandy seafloor to compose an interesting frame without sending plumes of particulates into the water column. I also needed to get within a foot or so of the octopus without causing it to flee or turn away from me. And, I had to maintain my buoyancy with breath control by altering the volume of air in my lungs.

Once I had captured a few frames, I needed to review my images by looking at the playback images on my camera’s LCD screen and then make any necessary adjustments to the settings for my camera and strobes, still without stirring up the seafloor or spooking the octopus.

Creating the seascape while diving at Verde Island near Puerto Galera in the Philippines required me to maneuver over a reef while not ascending, descending or bashing into the reef. I also had to maintain my position while dealing with a moderate current, remain neutrally buoyant once I was in position to compose my shot, monitor my depth, gas supply and remaining bottom time, and keep an eye on other divers or sea creatures that might become a distraction by entering my frame.

Of course, it can be just as important to be able to achieve and maintain neutral buoyancy when creating an image of another photographer working with a green sea turtle or when cruising over a reef while photographing a sea krait that is on the move. The same is true when it comes to photographing a feeding flamboyant cuttlefish you want to get close to without disrupting its feeding behavior or when approaching a mantis shrimp carrying a clutch of fertilized eggs.

I could go on and on with a list of subjects and shooting scenarios, but the point I hope to make is that no matter what your subject is, good diving skills are required to consistently create strong images. I hope you will take this message to heart and impart it with conviction to your students.