Manō, or sharks, help maintain the balance of ocean ecosystems as apex predators, but due to the perception of sharks as a dangerous threat to humans, they have not received the protections needed to sustain healthy populations. Research has shown that the media has a strong influence on an individual’s emotional reactions, threat perceptions, willingness to support conservation, and intentions to seek information. Individuals are more likely to have negative emotions, feel more threatened, and be less inclined to support conservation efforts or seek information if the media presents fear-based or negative information regarding a species. In contrast, positive media portrayal of sharks could reverse this trend and increase support for conservation actions.

Every day, sharks are slaughtered all around the world. Sharks are caught intentionally or as accidental “by-catch” in both commercial and recreational fisheries and remains the most frequent threat to sharks worldwide. Shark finning is another major threat and involves the removal of the animals’ fins to be used for medicinal purposes and in the traditional Asian dish of shark fin soup. Shark fins have become one of the world’s most valuable fishery products because of it. Sharks are also hunted for their liver oil, meat, and skin for consumption and to make various products, and a number are caught and killed for sport by people who fear them and lack awareness of their importance. This illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a leading threat to their survival, however, other human influences such as habitat degradation, coastal development, pollution, and negative media coverage have significantly affected their vitality.

Who should really be afraid?

While infrequent, unprovoked attacks on humans draw an enormous amount of media attention. Human impacts on sharks are much greater, with an estimated 100 million sharks killed each year by commercial fisheries alone. The current fate of sharks parallels the historical example of gray wolves in the United States. Wolves were culled to minimize predation on cattle and sheep and lower the chance of attacks on humans, nearly leading to their extinction in the 1800’s.

A difference in the way media is presented can drastically change how it is perceived. Documentaries tend to be more factual and accurate than the archetypal fictional and/or misconstrued information in many movies, shows, and news channels. Modern environmental documentaries aim to persuade individuals to preserve the environment by increasing the amount of factual information presented to viewers.

What Do Sharks Do for Us and Why Should We Save Them?

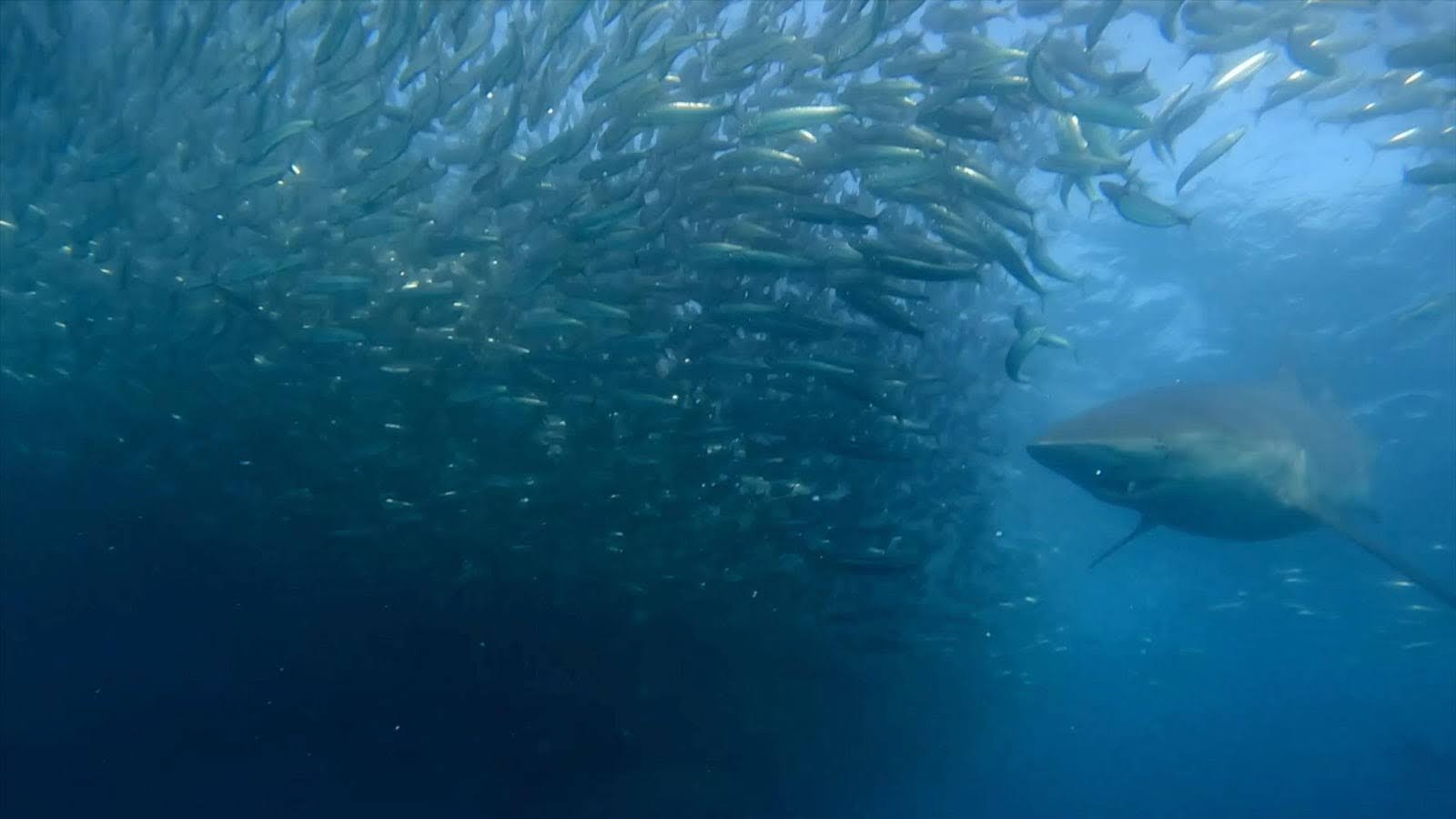

Sharks’ role as apex predators is to maintain the overall balance of the ocean by removing the sick and weak animals and ensuring population stability and species diversity lower in the food chain. Sharks exert “top-down” control on ecosystems, meaning that they have both direct and indirect impacts on organisms throughout the food chain. When healthy populations of sharks are removed from the ecosystem, other large predatory fish increase in abundance and overfeed on marine herbivores, like uhu and kole. As herbivorous species decrease, macroalgae expand and outcompete coral, shifting the ecosystem to one that is algae dominant. In an algae dominant environment, corals are more susceptible to bleaching events and Harmful Algal Blooms (HAB’s) are more likely to occur causing large numbers of deaths in marine organisms. As a result of this rapid increase in death and decay, oxygen is depleted from the water suffocating entire areas of ocean, known as dead zones. Consequently, this devastates the overall viability of coral reef systems that a quarter of all marine life rely on to survive.

Where designed in collaboration with local communities and utilizing best practices for minimizing impacts, shark ecotourism can also provide important local economic alternatives. Studies have determined that sharks are more profitable for people when they are alive in their natural environment. Oceana, a nonprofit ocean conservation organization, conducted an independent economic report in 2016 that found that the total economic contribution of shark encounters in the state of Florida was more than $377 million. Contrary to this statistic, the 2016 U.S. shark fin export market resulted in only $1.03 million. Shark ecotourism programs, several of which can be found locally, can help increase participants’ knowledge and foster positive environmental attitudes towards sharks. However, there is still much controversy around the shark tourism industry and whether or not organizations within the industry are following ethical tourism guidelines and whether they are designed in collaboration with local communities. Shark tourism practices vary by operation and location. It is important to identify which ecotourism programs are following proper guidelines to ensure the protection of sharks and humans. Strictly enforced shark tourism guidelines can help minimize impacts while providing an educational opportunity to see sharks safely in the wild.

The Historical, Cultural, and Ecological Significance of Sharks in Hawaiʻi

In Hawaiʻi, we are fortunate to have relatively stable shark populations. Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) have a strong cultural history of respecting sharks as important components of the ecosystem, as well as ʻaumākua, or spiritual members of a family that take the form of a specific animal or object. Tiger sharks (niuhi) are commonly revered as ʻaumākua because of their intellect, sensitivity, and role as a guardian of the ocean. Kāne‘ohe Bay on the windward side of Oʻahu is also known to be one of the world’s largest breeding grounds for endangered scalloped hammerhead sharks (manō kihikihi).

Shark Conservation in Hawaiʻi

Despite their significance in Hawaiʻi, sharks have minimal enforceable protection throughout Hawaiian waters and still face a number of threats. These include overfishing, accidental catch, and purposeful killing, with many cases reported on the North Shore of O‘ahu and in Kāne‘ohe Bay. At least one species, scalloped hammerheads, are classified as “critically endangered,” while other commonly found sharks across Hawaiʻi such as the tiger shark, sandbar shark, and oceanic white tip shark are near threatened, vulnerable, or endangered according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Fortunately, in 2019, Hawaiʻi state legislature introduced Bill SB489 relating to shark and ray protection. This bill would make it illegal to knowingly capture, kill, or abuse any species of shark or ray within Hawaiʻi’s waters. If this bill passes into a law, these crimes would be classified as a misdemeanor with penalties ranging from $500 to $10,000. In 2010, Hawaiʻi also passed an anti-finning law which bans the sale and possession of shark fins in the islands.

What Can We Do to Increase Protections for Sharks?

The decline in global shark populations has major consequences for economic stability and environmental sustainability and is ultimately a result of misunderstanding, fear, greed, and a lack of awareness and education. People will rarely protect what they fear, and an important part of shark conservation is dispelling the myth of the “mindless killer” by changing the way sharks are viewed. An estimated twenty-four percent of shark, skate, and ray species found around the world are listed on the IUCN Red List as “Threatened with extinction,” and that number is expected to increase if positive shifts in human actions, perceptions, and fishing practices are not made.

Education about this important socio-ecological issue will help individuals have more positive perceptions and experiences with sharks in the future. This will encourage people to make more informed choices related to politics and consumerism that benefit sharks and their protection. Actions as simple as choosing factual media, such as documentaries over fictional movies, participating in beach and reef clean-ups, reducing seafood consumption or opting to support sustainable local fisheries over commercial, refusing and reducing plastic usage, and sharing positive stories regarding sharks can have a tremendous impact on their populations.

On a larger scale, implementing informational signage at public beaches and institutions that outline the ecological and economical importance of sharks, shark behavior, and other holistic shark safety strategies could result in human risk reduction, public awareness, and shark conservation. Stricter regulations can be established and enforced regarding unsustainable commercial and recreational fishing practices, and the incorporation of shark safety and education programs that acknowledge human concerns could aid in long term shark conservation efforts.

Public interest in shark ecotourism and conservation organizations reveals people’s true fascination with these living fossils. Education and policy will hopefully foster more positive perceptions and experiences with sharks in the future and will encourage people to make more informed choices that benefit sharks. Taking the time to understand these misrepresented creatures can be extremely beneficial to their protection and will subsequently benefit humans as well.

===========================

Photo credit: Juan Oliphant from One Ocean Diving

Author’s Bio: Laura received her Bachelor’s in Marine Ecology and Conservation from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and is currently pursuing her Masters in Conservation Biology through the Miami University of Ohio’s Global Field Program. As an avid conservationist and nature enthusiast, she actively volunteers with a local non-profit organization, Sustainable Coastlines Hawaiʻi, to help keep Hawaiʻi’s beaches clean and educate community members about plastic pollution. When she’s not at work, studying, or volunteering, you can most likely find her outdoors; at the beach, in the water diving or surfing, or hiking up a mountain. Her love of and interest in taking care of the environment around her stems from being born and raised on Oʻahu.